Residents and local officials in the Catskills are celebrating an agreement that puts an end to part of a decades-long land acquisition program by the New York City Department of Environmental Protection to protect the watershed of the city’s reservoirs in upstate New York.

For more details, we spoke to Meg McGuire, the founder and publisher of Delaware Currents, the news project dedicated to telling the story of the Delaware River from its headwaters in the Catskill Mountains of New York to the Delaware Bay, where it meets the ocean.

Ric Coombe, chairman of the Coalition of Watershed Towns, which was formed in 1991 to bargain with the DEP, confirmed that the parties had reached an agreement for the city to stop purchasing land in the majority of the Catskills watershed.

“This will be a turning point in reducing” land purchases, Coombe said. “It will take away that pressure to upstate communities that the city’s purchasing land has applied.”

The DEP also confirmed the decision to Delaware Currents.

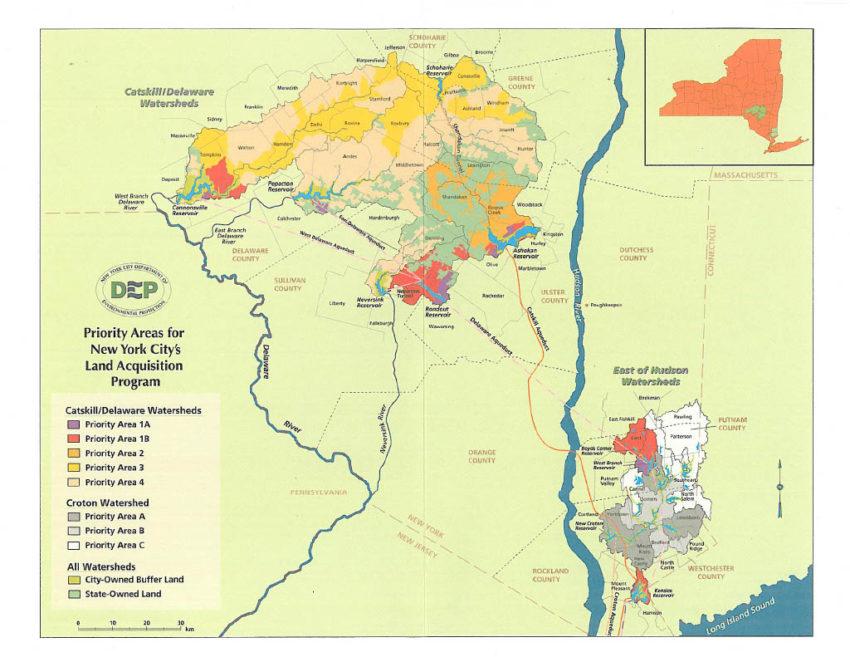

“There will be no more priority three and four acquisitions, which is most of the Greene County land area in the watershed, but additional focus on priority areas one and two,” John Milgrim, a DEP spokesman, said in an email. “Through a collaborative process and guided by science, DEP intends to focus resources on programs and acquisitions most beneficial to water quality protection while continuing investments to enhance the socio-economic vitality of our community neighbors.”

Priorities are shifting

Priority areas three and four make up the majority of the Catskills, including Greene and Schoharie Counties.

The majority of Delaware County is also part of these areas, as well as smaller chunks of Sullivan and Ulster Counties. Priority areas one and two are smaller in size and include parts of Ulster and Sullivan Counties near the Roundout Reservoir and in Delaware County near the Cannonsville Reservoir.

Read more: How the town of Cannonsville became the Cannonsville Reservoir

“The priority areas have been identified based on the location and makeup of the lands and the direct potential to threaten the New York City water supply,” the Delaware County Board of Supervisors said in a statement.

“Priority areas one and two include lands that are contiguous to the reservoirs and the infrastructure supporting the water transmission systems, making them more sensitive and therefore requiring substantially greater protection,” the supervisors said. “Therefore, the program will allow for NYC DEP to solicit lands for acquisition and advance contracts from willing sellers in these priority areas.”

Coombe attributed the long-awaited breakthrough to a change in New York City personnel.

“The city recognized that the core land-acquisition plan did need to change, which they had told us previously that they were going to change it … but they were seeking patience because they needed to change their approach to watershed protection,” he said.

Read more: Marist College students create a video about New York City’s reservoirs

Land purchase plans stirred opposition and concerns

New York City in 1997 rolled out the program across Delaware, Greene, Sullivan, Schoharie and Ulster Counties to protect its drinking water supply, which serves over nine million people and provides 1.1 billion gallons of water a day to the city and Hudson Valley communities.

From the beginning, critics worried about stunted economic growth of the area and a loss in property tax revenues. A lot has changed since a landmark memorandum of agreement was reached in 1997 after many years of complex and difficult negotiations between the city DEP and the affected counties.

One of the biggest turns in the process came when the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine conducted a full review of the watershed protection program that revealed that approaches like stream bank protection work and riparian buffer plantings could be more useful in protecting the city’s water than land acquisition.

The findings aligned with concerns of local residents and served as the backbone of continuing conversations.

“It was a good third party that led all parties to understand the science behind it,” Coombe said. “The report helped reinforce our position, especially when it came to the lower priority land of areas three and four.”

The Delaware County Board of Supervisors said that “the shift in policy is a result of many years of analysis and a comprehensive understanding of how land acquisition benefits water quality and the impacts it has had on community vitality.”

Read more: Tensions persist over NYC reservoir land protection more than 25 years after pact

Talks continue

Earlier this year, officials nodded to a light at the end of the tunnel between New York City and Catskills localities about the city’s land-buying to protect its watershed in the region.

Coombe told Delaware Currents in February that negotiations were “moving in good faith” and that both sides had made “very encouraging progress.”

Now, they can celebrate the changes that affect large portions of the Catskills, but talks are not over.

“Talks are continuing but the major land acquisition pieces have consensus agreement among stakeholders,” Milgrim said.

Coombe doubled down that there is still a lot more to consider. “We’re partners for life, whether we like it or not,” he said.

The agreement doesn’t eliminate other pressures, like the next generation of land management, which the Coalition of Watershed Towns hopes includes swapping lower- priority land for higher-priority land.

“This agreement stops them from filling their bucket, but we need to have them also let some out of it, which will take a much longer time,” Coombe said.

This article originally appeared on Delaware Currents.

Image: A map depicts the Catskills reservoir watershed and the priority areas for protection.