This story originally appeared in New York Focus, a nonprofit news publication investigating power in New York. Sign up for their newsletter here.

CRIMINAL JUSTICE · February 13, 2025

DAs Promised to Help Wrongfully Convicted New Yorkers. In Many Cases, They Made Things Worse.

Our investigation identified dozens of cases in which a wrongful conviction unit denied someone’s application, only for a judge to later exonerate them.

By Ryan Kost and Willow Higgins , New York Focus

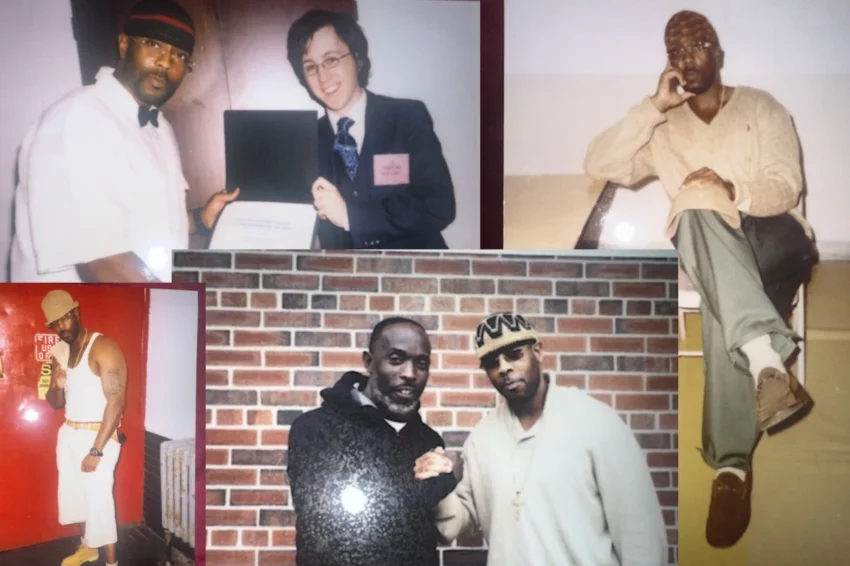

Calvin Buari had served nearly half of a 50-year prison sentence for a double homicide he didn’t commit when, in 2015, prosecutors in the Bronx District Attorney’s Office asked him to stop fighting his conviction.

His attorneys had recently submitted a court motion seeking to overturn it based on new updates in his case. Five new witnesses had come forward to identify another murder suspect and offer Buari an alibi for the decades-old crime that left two men dead, slumped over in a car near the east Bronx.

The prosecutors proposed an alternative to Buari. A new special unit in the DA’s office, called the Conviction Integrity Bureau, was starting to investigate wrongful incarceration claims outside of the court system — and his case seemed ready-made. They promised a fair and independent review, a collaborative fact-finding mission.

But during that review, the bureau’s investigators showed up at the witnesses’ homes and workplaces unannounced. Their aggressive inquiries prompted the eviction of one witness from the domestic violence shelter where she lived. Another witness was so distressed by her encounter that she asked her doctor to write a note detailing her heart problems in case she needed it in court.

The tactics reminded Buari of the witness intimidation that he believes stymied an earlier attempt to clear his name. He began to question the bureau’s motives. “It made me see that these people would do anything just … to try to sabotage truthful evidence from coming forth,” he said.

In January 2017, a year after the bureau’s official inquiry began, he received a letter denying his innocence claim.

Buari then turned back to the court. Within four months, a New York judge threw out his conviction.

The Bronx County bureau is one of 17 conviction integrity programs across New York, which has more than any other US state except California. The units, typically housed within DAs’ offices, were created over the past decade, during a national wave of criminal justice reform, to re-examine criminal convictions that those DAs may have gotten wrong in the first place. New York’s DAs have ushered in CIUs, as they’re commonly known, with high hopes and bold promises.

In 2015, while vowing to launch her own program, then–Bronx County DA candidate Darcel Clark reportedly called the units “standard operating procedure” in any modern DA’s office.

“Justice is justice,” she said at the time. “And this review is part of justice.”

Sandra Doorley, Monroe County’s top prosecutor, described her county’s CIU as a way to “help with a fair and just criminal justice system.”

“Convicting innocent people is a horrifying concept,” she said.

New York’s conviction integrity programs have fallen short of their promise, an investigation by New York Focus and Columbia Journalism Investigations found. Nearly half of them have yet to support a single exoneration. The 12 CIUs outside of New York City — which have been around for an average of six years each and collectively boast three dozen staff members — have only supported 12 exonerations between them.

Here’s what else we found:

- New York’s CIUs did not support the claims of 14 defendants whose convictions were later overturned by the courts because of newly discovered evidence; 11 saw their convictions vacated because the court found their constitutional rights had been violated.

- In more than 40 percent of the total cases analyzed, the prosecutor who handled the original criminal case was still working at the DA’s office during the CIU reinvestigation, requiring CIU personnel to re-examine their colleague’s past conduct.

- In half a dozen cases, defense attorneys and witnesses raised concerns about CIU staff, including allegations of intimidation and coercion.

Interviews with dozens of people and a review of hundreds of pages of government records reveal a CIU system operating almost entirely in secret, with no outside oversight. Most units across the state answer solely to the DAs who created them. Controlled by elected officials, units can become vulnerable to internal pressure to cover up past mistakes. And because there are no legal standards governing CIUs, personnel can commit the same abuses as their colleagues in DAs’ offices — to the detriment of the wrongfully convicted.

Applicants in New York have found the CIU process slow and haphazard, leaving them in limbo, sometimes for years, awaiting a response. More often than not, units denied the applicants identified in this investigation without a review, or rejected them after a reinvestigation without explanation.

New York Focus and CJI analyzed data from the National Registry of Exonerations, reviewed every known exoneration case in a New York county with a CIU, and interviewed more than 100 exonerees, defense attorneys, legal scholars, current and former CIU staff members, and elected district attorneys in order to evaluate the units’ efficacy. The investigation identified at least 27 defendants in the state, including Buari, who did not win support from a county CIU, only to have their convictions overturned by the courts later.

That’s one in every six exonerations since 2010 in the New York counties that have such units, according to a New York Focus and CJI analysis of national exoneration data. In most instances, CIU staff had access to the same information that prompted the judge to act.

The vast majority of cases involve Black and Latino defendants from across the state, including New York City, the Hudson Valley, and western New York. Because they applied to a CIU, they spent more time fighting their wrongful convictions than if they had gone to a judge in the first place. In a few cases, the process took months. On average, however, it took more than three years. All told, defendants spent an average of 19 years in prison before clearing their names.

It’s difficult to know just how many wrongful conviction cases were dismissed or rejected by CIUs only to be upheld by courts later, because New York seals exonerees’ names in court records. In response to records requests, most of New York’s CIUs declined to provide applicant lists or provided partial lists. Reporters filed more than 100 records requests seeking basic information about how New York’s CIUs operate. Most units failed to respond.

In interviews, some district attorneys defended the work of

CIUs. Former Erie County District Attorney John J. Flynn, who headed

the District Attorneys Association of the State of New York from June

2023 to March 2024, said that a judge’s decision in a wrongful

conviction case does not determine how effective the CIU is because

judges and DAs don’t always agree.

“You’re not going to win every case,” said Flynn, who

resigned from Erie’s top prosecutor post earlier this year after two

terms. “That’s how the legal system works.”

But some CIU proponents admitted that the investigation’s

findings cast doubt on the programs’ ability to live up to their

mission. The gap between CIU and judicial decisions could signify that

these units lack resources or that their review process has broken down,

one expert said, but it could also indicate that New York’s DAs don’t

evaluate wrongful conviction claims objectively.

“That’s a way of showing that these units — some of them at

least — are not functioning properly,” said Barry Kamins, the former

chair of the New York State Bar Association’s wrongful convictions task

force, which in 2019 recommended that all 62 county district attorneys’

offices create conviction integrity programs. Kamins, a retired judge

who now serves on a different statewide wrongful conviction task force,

noted that some DAs believe that their offices never make mistakes and

only convict guilty people.

“That’s unfortunate,” he said, “and that’s why there should be some structure in place to look at convictions.”

Failing Best Practices

New York’s conviction integrity programs, which are among the oldest in the US, have expanded rapidly since 2010. Today, more than a dozen county DAs’ offices have one, and in just the last year, three newly elected DAs have pledged to create bureaus.

The basic model is simple: Defendants who believe they were wrongfully convicted can apply to have their case reviewed. The CIU decides if an application has merit and then launches a reinvestigation in which prosecutors weigh newfound evidence and may interview witnesses. If the CIU determines that a defendant is innocent, the DA’s office can support a motion to overturn the conviction. Throughout this process, the unit works with defendants and their attorneys, rather than against them.

Some units have a formal structure with designated staff. Others consist of informal panels of volunteers. Smaller DAs’ offices may have an ad hoc review process rather than a separate unit. All operate under the premise that prosecutors and police can make mistakes that put the wrong people behind bars.

The rise of CIUs in New York aligns with a national movement for justice reform led by so-called progressive prosecutors aiming to correct wrongful convictions. Studies estimate that innocent people could comprise as much as 6 percent of the US prison population. That would translate to approximately 2,000 incarcerated people in New York alone.

Their path to exoneration is narrow. While defendants can appeal their convictions, appellate courts rarely overturn them. From 2007 to 2023, New York appellate courts reversed a conviction and then dismissed the indictment — the equivalent of a full exoneration — in less than 3 percent of all felony appeals, according to the justice reform group Scrutinize. Once defendants have exhausted their appeals, their options dwindle, making conviction integrity units a crucial last resort.

New York CIUs do not publish annual statistics about their caseloads, so it’s difficult to know whether they offer wrongly convicted defendants a better chance at success. The national exonerations data shows that conviction integrity units supported exonerating 93 incarcerated people between 2010 — when the state’s first one was created in Manhattan — and 2024. That accounts for roughly 60 percent of the total exonerations that have taken place in counties with CIUs.

Charles Linehan, who headed the Kings County CIU in Brooklyn from 2022 to last month, considers the unit a national leader and noted its role in roughly 40 exonerations so far. “Admitting when we’ve got it wrong in the past and correcting those mistakes is, to me, a huge indicator of success,” he said. The Brooklyn unit is one of only two in the state with an outside panel that reviews the unit’s findings and makes a final recommendation to the DA.

While a CIU’s process varies from county to county, experts have laid out best practices to ensure independence and impartiality — and most of the state’s programs fail to live up to them.

‘Harassing and Intimidating’ Witnesses

Buari has had an entrepreneurial spirit all his life. As a

child, he sold homemade cookies at school and walked groceries to

people’s cars for tips. By age 12, his friends had begun selling drugs.

Seeing an opportunity to help out his single mother — and buy the

Jordans that the cool kids wore — Buari joined them.

When Buari heard gunshots that day in 1992, he started

running. He was “just trying to get out the way,” he said. By then, he’d

established himself as a local dealer, and tensions had risen between

rival outfits on his east Bronx block. Two men died in the shooting, and

Buari’s life would never be the same.

Buari told police he had been near the crime scene, but the

gunshots sent him running. Prosecutors didn’t believe him and promised

leniency to several drug dealers in exchange for testimony that was used

to convict Buari. He was arrested in 1993 and found guilty of

second-degree murder two years later.

After nearly a decade of his own legal work, Buari filed

his first innocence claim in 2003, when a dealer who had testified

against him confessed to the crime. But the dealer later recanted under

questioning from investigators with the Bronx DA’s office.

When the Bronx CIU reinvestigated Buari’s case more than a decade later, his attorneys brought it to the attention of then–DA Darcel Clark. In a January 2016 letter, defense attorney Myron Beldock told Clark that he believed the case “qualifies for your personal attention in carrying out your stated mission to see that justice is done.”

The Bronx assistant district attorneys assigned to the CIU effort vowed to conduct a “fair, impartial, and non-adversarial” review, Buari later claimed in a civil lawsuit.

But his attorneys soon heard that the investigators were intimidating witnesses.

Among them was Nakia Clark (no relation to the DA), a key witness for Buari’s innocence claim. On the night of the shooting, Clark, then 17, was outside her sister’s house when she saw a man shoot a gun into a car. She still remembers how the victims’ bodies jerked. At the time, Clark didn’t tell anyone what she observed; her sister had warned her not to speak to cops.

Two decades passed before Buari’s family would post notices about the case in the neighborhood and an investigator they had hired would find Clark and other new witnesses. Clark agreed to speak with authorities if an attorney accompanied her.

“At the end of the day, it’s me. If they disagree with me … that’s kind of too bad.”

—John J. Flynn, former Erie County district attorney

When CIU investigators contacted her in the summer of 2016, she’d just found a room at a domestic violence shelter in Kingston. The investigators showed up without notice, violating the shelter’s women-only rules. A shelter employee later told her that she would have to leave the facility — the one place offering her counseling, clothing, and other essentials — in order to guarantee its residents a safe space, she said. Clark had to pay for a hotel room out of pocket until she could find housing. Clark said she felt pressured by the CIU investigators and

remembers them warning that she could get in trouble if she testified.

“It seemed like a threat,” she said in an interview. “Like

if I testified and said the wrong thing, that I could wind up getting

locked up.”

Both Clark’s sister and a third witness, Caroline Brown,

also reported feeling intimidated by the investigators. Brown, who had

learned about Buari’s wrongful conviction claims through a news article,

called their behavior “harmful” to her health, according to Buari’s

legal filings. The experience prompted her to bring a doctor’s note

detailing her heart and anxiety conditions to a court hearing months

after her CIU interview, in case she needed it.

The tactics ran counter to defense attorneys’ expectations.

Records show Beldock had told the Bronx DA that the witnesses wanted

legal representation during their CIU interviews. Another of Buari’s

defense attorneys sent an email to a prosecutor overseeing the

reinvestigation to raise concerns about the investigators’ “harassing

and intimidating” conduct. The prosecutor did not respond to his

concerns.

A spokesperson for the Bronx DA’s office declined to make the employees who worked on Buari’s CIU case available for interviews for this story. It’s unclear whether the office looked into the witnesses’ allegations about the investigators’ behavior or whether there were any consequences as a result; the office provided a written statement about the case but declined to comment further.

DA Clark, for her part, did not respond to a request for comment for this story, and the office’s spokesperson declined to make her available for an interview.

In the statement, the office acknowledged that its reinvestigation had “unique challenges” and noted that an earlier judicial ruling had accused Buari of intimidating witnesses — accusations that a different judge later discounted, records show. The office also questioned why any eyewitness to a murder would “feel the need for the services of an attorney.”

The Bronx CIU ultimately rejected Buari’s exoneration bid, stating that the new evidence didn’t prove “the conviction was wrongfully obtained,” the unit’s January 2017 letter to Buari stated.

Three months later, based on the same evidence that led the CIU to

reinvestigate it, a judge vacated Buari’s conviction and ordered a new

trial. In his written decision, the judge excoriated the way the Bronx

CIU had treated the Clark sisters and Brown.

Their “involvement has only served to draw unwanted attention, and hostility from the Bronx District Attorney’s Office,” he wrote, noting the trouble that investigators had caused Nakia Clark and the way prosecutors had questioned Brown’s past drug use to discredit her. He called their treatment of Clark, in particular, “unconscionable.”

The ruling released Buari from prison. It took another 10 months for the Bronx DA’s office to dismiss the charges, making his exoneration official.

In an interview, Buari called his CIU experience “a waste of time.”

“They felt like I was a drug dealer, so I didn’t matter,” he said.

Not One Exoneration

Buari had reason to believe things would be different. As part of Darcel Clark’s 2015 district attorney campaign, she had promised to create a CIU in the Bronx. She was one of eight New York DAs to do so during an election bid over the past decade. In Monroe County, home to Rochester, four-term DA Sandra Doorley made similar promises during two of her campaigns; she established a CIU amid a contested reelection in 2019.

“We aim for justice,” Doorley said at the time, “not incarcerating as many people as possible.”

She tapped an assistant prosecutor to oversee the unit’s operations, and, in line with best practices, assembled a committee of nine volunteers from inside and outside the office — retired police, a retired judge, and two residents — to collaborate with the unit chief and conduct investigations.

Monroe CIU members fielded a flurry of applications early on, according to records and interviews, including one from Anthony Miller, who was serving time in Wyoming Correctional Facility in western New York.

“It seemed like a threat. Like if I testified and said the wrong thing, that I could wind up getting locked up.”

—Nakia Clark, a witness interviewed by Bronx CIU investigators

In 2013, Rochester police arrested Miller, then 21, after

receiving a report of a Black man in a hooded sweatshirt robbing another

man at gunpoint of a phone, $10, and cigarettes. Court records suggest

officers detained him simply for being the first Black man wearing a

hoodie they found. He was chatting with a friend half a mile from the

crime scene.

Prosecutors indicted Miller for armed robbery and offered

him a plea deal of three and a half years. Miller declined, maintaining

his innocence. In 2015, he got 10 years instead.

Earlier in his sentence, Miller asked the DA’s office if

there was a conviction integrity unit, and was told no. When Doorley

announced the creation of one, Miller saw it “as a sign from God,” he

said in an email, and applied for a reinvestigation in June 2019.

In a letter to legal advisers that month, Miller said that

he hoped Doorley’s CIU would amount to more than mere lip service. “The

pain and suffering is legit when it comes to being imprisoned for a

crime you did not do,” he wrote.

Three months later, he learned that his application was

under review. It was the first case Doorley’s CIU reinvestigated,

according to sources familiar with the process. But it wasn’t the

godsend Miller had hoped for.

During the review process, the DA’s chief investigator

recognized holes in the initial investigation, records show: Though the

robbery victim identified Miller, it was out of a lineup of one, and a

police dog had tracked the robber’s scent to a different location.

Police did not find any of the stolen items on Miller when searching him

just minutes after the crime had occurred.

Miller’s CIU case file suggests other possible gaps. Around the time Miller applied for a case review, a local attorney named E. Robert Fussell contacted the unit. He was representing a woman who had sued the same officers for beating her up and shooting her dog during an arrest. Their treatment of his client led Fussell to believe “that they were not above setting up Mr. Miller,” he wrote in a letter to the CIU.

Records show Fussell called Dan Gross, the Monroe CIU coordinator, and described the officers’ cruel conduct and false arrest. After that initial phone call, no one at the unit followed up, Fussell said in an interview.

That fall, Gross rejected Miller’s CIU application — though there were disagreements among committee members, according to Wayne Harris, a former committee member and retired police officer. “I thought we should probably move for a vacated conviction,” he told New York Focus, but others did not concur.

Gross, now a law clerk in Monroe County, declined to comment.

In June 2020, Doorley’s chief investigator revisited the Miller case at Gross’s request. But the investigator and Doorley agreed to keep it closed after unsuccessful attempts to discuss the case with Miller’s parents.

Doorley declined interview requests for this story.

In November 2020, a year after the CIU officially had closed the case, the court overturned Miller’s conviction and dismissed his indictment. The judge cited “considerable, objective evidence” of his innocence — the same evidence that the CIU had found insufficient earlier.

“The pain and suffering is legit when it comes to being imprisoned for a crime you did not do.”

—Anthony Miller, whose exoneration bid was rejected by the Monroe CIU

The current Monroe CIU chief, Scott Green, has since

restructured the unit, opting for a smaller panel because he believed it

would be more effective. At least 71 defendants have applied to the

Monroe CIU over the past five years, he said. The unit has not supported

any exonerations.

Green defended this record, saying it suggests that the

original convictions were correct and that “things have been done

properly.”

To Harris, the former CIU member, what happened in Miller’s

case suggests otherwise. “I am disappointed by how Rochester’s effort

on conviction integrity turned out,” he said.

In October, a judge awarded Miller $3 million for his

wrongful conviction. Miller learned about the ruling while in prison for

charges stemming from a drinking and driving incident, which he

attributes to his wrongful conviction.

He was “just a little lost,” Miller said, after six years

in a penitentiary. “That’s what led to the drinking … and that’s what

led to my downfall.”

‘At the End of the Day, It’s Me’

New York’s elected DAs control nearly all of the conviction review process. In all 17 county CIUs, the DA appoints the unit chief, determines how to allocate the budget, and decides whether to support an exoneration. They can also shut down a CIU reinvestigation at any moment — or disregard a unit’s recommended action without any explanation.

That’s what happened at the Erie County DA’s office in March 2021, when James Pugh and Brian Scott Lorenz moved to overturn their 1994 murder convictions for a homicide in Tonawanda, a city just north of Buffalo. While Lorenz had initially confessed to the crime, he soon recanted. Pugh had always maintained his innocence.

In their 2021 motions, defense attorneys argued that the men’s convictions should be tossed because new DNA tests on evidence collected from the crime scene eliminated both as culprits. They also accused the lead Tonawanda detective of coercing and bribing witnesses during the original investigation.

In response, then–Erie DA John J. Flynn ordered a full reinvestigation of the case, led by two senior assistant district attorneys who had worked on several of the office’s reinvestigations. Already, the two prosecutors had helped five incarcerated people overturn their convictions. Flynn, who served as the Erie DA from 2017 to March 2024, had twice commended one of the prosecutors for this work.

The pair spent four months conducting dozens of interviews, including with Pugh and Lorenz.

“I’d been waiting so long for somebody to just sit there

and say, ‘Tell me what happened. Let me hear your side,’” Pugh said. He

remembered leaving the three-hour conversation thinking that he might be

able to clear his name.

The prosecutors concluded that he and

Lorenz were innocent. In addition to the lack of DNA evidence, they

uncovered evidence withheld from the defense during the original trial.

They also heard testimony that led them to question the case’s lead

officer, their CIU investigative files show. At least a dozen people,

including some former co-workers, had expressed concerns about the

officer’s conduct or disposition.

“Not trustworthy, honest,” one prosecutor wrote in his notes, referencing what the officer’s colleague had said.

In an email to New York Focus, the officer denied that he had coerced or bribed any witnesses and blamed the statements questioning his honesty on a jealous co-worker. “I was a much decorated police officer due to my ability to solve cases,” the officer wrote. “Most complaints about me were from the many criminals I arrested.” A copy of his personnel file, obtained through a records request, shows that the officer later retired from the Tonawanda Police Department after it had received two complaints about his behavior on an unrelated case.

In August 2021, the prosecutors had submitted their findings to Flynn. They were preparing a presentation for the office’s top deputies when Flynn canceled it without explanation. He later called the prosecutors into his office and upbraided them, according to court testimony.

“It made me see that these people would do anything just … to try to sabotage truthful evidence from coming forth.”

—Calvin Buari, whose exoneration bid was rejected by the Bronx CIU

One prosecutor, who was demoted to line assistant and still

works in the Erie DA’s office, did not respond to multiple interview

requests. The other left the office in late 2021 and now works as a

public defender in the county. He declined to comment, but in a December

2021 hearing on Pugh’s and Lorenz’s motions, he testified about what

had happened in Flynn’s office.

According to his testimony, Flynn voiced concerns over the

CIU’s findings and made it clear that the office would oppose the

exoneration motions. The Erie DA worried aloud about public fallout from

accusing a retired officer of coercing witnesses to give false

statements and other possible misconduct.

Flynn said “he couldn’t go in front of the cameras and say

that a retired detective was involved,” the prosecutor recalled in his

testimony.

In an interview with New York Focus, Flynn said he found

the allegations against the officer unconvincing. “I’m not going to

publicly accuse anyone of misconduct if there was no misconduct,” he

said.

Flynn referred to a previous statement released by the DA’s

office, in which he denied that he had reassigned the two prosecutors

“because I did not agree with their findings.” Rather, he accused them

of not accepting “my decision with the professionalism expected of

career prosecutors.”

Pugh saw things differently. “Their own people believed in me,” he said, but the elected DA “refused to believe them.”

Sara Ogden, who headed the Erie CIU from its formal creation in 2018 until 2020, described the prosecutors as smart and well respected in the office. She said she would have trusted both to conduct a thorough and fair reinvestigation.

In August 2023, a trial court judge overturned the convictions of Pugh and Lorenz, citing the evidence that the prosecutors had uncovered during their reinvestigation. The DA’s office appealed, but an appellate judge upheld the ruling in September 2024, and a higher court declined to review that decision. The DA’s office has since moved to retry the men.

“I’d been waiting so long for somebody to just sit there and say, ‘Tell me what happened. Let me hear your side.’”

—James Pugh, whose case was reinvestigated by the Erie DA’s office

For Pugh, previously released on parole, the years lost to the justice system have taken a toll.

“Waiting to get married, buy a house … that’s all over,”

said Pugh, now in his sixties. Referring to the Erie DA’s office, he

added, “They’re just waiting for me to pass away so they don’t have to

deal with it.”

Michael Keane, who oversaw the Pugh and Lorenz

reinvestigation, is the newly elected Erie DA. He declined to comment on

the case.

Last March, just a week before stepping down as DA, Flynn

said in an interview that the final call on CIU decisions should belong

to the elected prosecutor.

“At the end of the day, it’s me,” said Flynn, now in private practice. “If they disagree with me … that’s kind of too bad.”

‘What Type of Integrity Is There?’

Five years ago, when the state bar association convened its wrongful convictions task force, it called for every district attorney in the state to launch a CIU. Task force members outlined a set of standards for how the units should operate and urged state lawmakers to establish a fund that would help DAs jumpstart the programs.

“We were hoping it would resonate,” said Kamins, the task force’s co-chair. But he said the state did little to advance the recommendations.

Kamins’s concern, beyond whether New York’s existing CIUs are operating properly, “is why so many DAs have not issued them at all.”

Other reformers said there’s little point in mandating more CIUs without addressing the existing units’ flaws. Families and Friends of the Wrongfully Convicted, or FFWC, which pushes for greater support for exonerees, has called on New York City councilmembers to provide more funding for and direct supervision of the city’s CIUs. The group has also asked each of the city’s units to provide information on their annual caseload, to no avail.

“If the [CIUs] are not functioning right, it makes no sense to have one,” said Kevin “Renny” Smith, FFWC’s executive director.

Last May, the New York City Council public safety committee summoned CIU chiefs to a hearing, where they touted their efforts to overturn past wrongful convictions.

Smith has attended many similar hearings and seen little

change, he said. He’s become convinced that local and state officials

should provide additional funding to CIUs in exchange for strong outside

oversight and uniform operating procedures that guarantee greater

transparency, like required annual reports on case outcomes and

exoneration rationales.

Such reforms would be too little, too late for exonerees

like Buari. In the nearly seven years since he cleared his name, he

filed a federal lawsuit against the Bronx DA’s office and others

alleging civil rights violations, as well as a state claim for

compensation for his wrongful imprisonment. He’s settled both and

received $7.75 million for the 21 years he spent in prison.

Ever the entrepreneur, Buari has put some of the money into

his brother’s Bronx auto detail shop and started a shuttle service to

transport family and friends of incarcerated New Yorkers to remote

correctional facilities across the state. But the money can’t make up

for not being able to say goodbye to the loved ones he lost while in

prison, Buari said — like the godmother who raised him, or the lawyer

who became a father figure.

Buari believes that cooperating with the Bronx CIU added

another year to his unjust sentence. While he’s not ready to write off

these programs yet — the wrongfully convicted should “do whatever they

can to try to get some type of relief,” he said — his experience has

taught him that DAs’ offices can’t police themselves.

Until the CIU process is independent, Buari said, it won’t be impartial. “The right thing is never going to be done.”

Ryan Kost and Willow Higgins reported this story for

New York Focus. CJI reporting fellows Curtis Brodner and Oishika Neogi

contributed to the data reporting and analysis. New York Focus and CJI

provided editing, fact-checking, and other support.

This project was completed with the support of a grant

from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil

and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures.

Additional support was provided by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

That’s great that there’s people to help the wrongfully convicted. Please help Avery Green. He’s in Auburn Correctional Facility.