This story originally appeared in New York Focus, a non-profit news publication investigating how power works in New York state. Sign up for their newsletter here.

THERE’S A RED HOUSE on Penny Place with three bedrooms, a fireplace, and baby pink tile in the bathroom. In 2022, Ulster County foreclosed on the home, in Ellenville, after the owner failed to pay a $13,390 tax bill. A company called Blue Door Housing bought it in a public auction for $103,200, and the county earned nearly $90,000. The former owner was left with nothing.

“It’s really, really devastating for people who have worked for 30 or 40 years to pay off their mortgage to lose this money this way,” said Tanya Dwyer, a foreclosure lawyer in the Hudson Valley. “It’s their retirement safety net. It’s the generational wealth their family has been building by protecting the house.”

Last May, the United States Supreme Court ruled the practice unconstitutional in Tyler v. Hennepin County, arguing that a municipality keeping the surplus money in a tax foreclosure sale violates the takings clause of the Fifth Amendment. In 2015, Geraldine Tyler, an octogenarian living in Hennepin County, Minnesota, had her condo foreclosed on after failing to pay a $15,000 tax bill. The county sold her condo for $40,000 and kept the surplus $25,000, leaving Tyler — like the former owner of the house on Penny Place — with nothing.

New York was one of more than a dozen states that had this practice in place. Then the scotus ruling came down, making its inclusion in state property tax law unconstitutional.

While this was good news for former homeowners, it has left local governments and land banks in limbo as they wait for the state to amend the law. Dwyer is asking municipalities to return the money they’ve taken from her clients over the years, arguing that New Yorkers are owed the homes’ fair market value at the time of foreclosure. County officials, meanwhile, are asking lawmakers to invest in foreclosure prevention programs and for the money to fill the newfound holes in their budgets.

“The problem lies after respecting the decision,” said Kevin Gardner, president of the New York State County Treasurers and Finance Officers Association. “We have the surplus funds, but we still paid a lot of money to prepare ourselves through the foreclosure. So how do we get reimbursed for that?”

EVEN THOUGH they’re subject to state law, New York municipalities each conduct tax foreclosures their own way. As a result, the state doesn’t keep data on how many tax-delinquent properties have been foreclosed on, how much money local governments have kept from foreclosure sales, or how the demographics of foreclosed homeowners look.

In the Hudson Valley, Dwyer said, more than 2,000 properties have been foreclosed on over the past two years after owners failed to pay their taxes. Across seven counties, she estimates that $20 million in surplus funds are taken from property owners annually. Her typical client owned a home worth more than $250,000 and owed $15,000 in taxes.

“A lot of our clients are elderly, often widows, who have very modest Social Security income and perhaps a small pension, but they can’t pay their taxes just on Social Security income,” Dwyer said. “The taxes are usually $10,000 a year. They wouldn’t be able to eat or go to the doctor if they used their Social Security income to pay their taxes.”

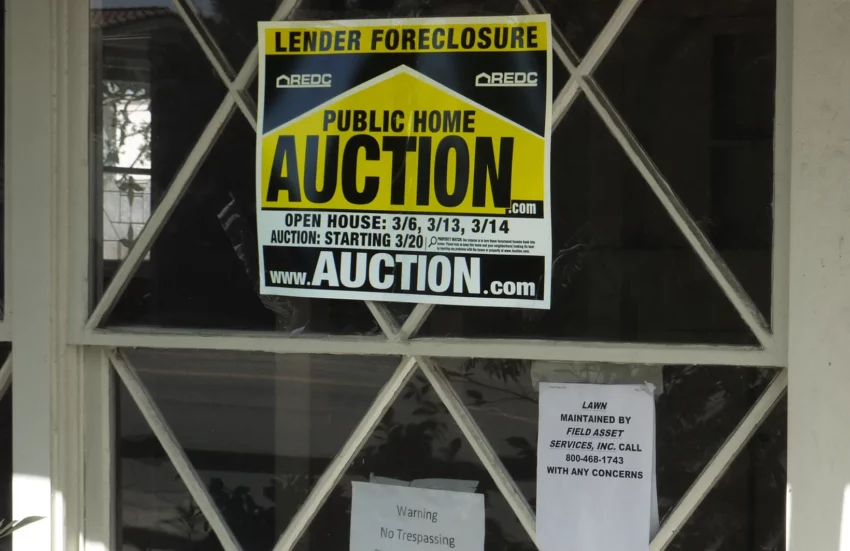

Many people’s properties represent their life savings. If they fail to pay their taxes and their house gets foreclosed on, they get evicted, and their local government may sell their house in a public auction. After taxes, interest, and administrative fees, they might expect to use the surplus money to find new housing.

Pre-Tyler, that surplus would go into a municipality’s general fund. In the decision’s wake, they have to give it back — and Dwyer is looking to make that retroactive. She’s asking towns, cities, and counties in the Hudson Valley to return the money to her clients and everyone else who has faced tax foreclosure.

“They wouldn’t be able to eat or go to the doctor if they used their Social Security income to pay their taxes.”

“The amount owed to them is the fair market value of the home the day the deed was taken,” Dwyer said. “So if the auction amount is less than fair market value, then municipalities must find money to pay homeowners the shortfall.”

Even if the retroactive window only went back for a year or two, “that could be devastating if you’re a municipality that may have collected millions of dollars and spent it already,” said David Wilkes, a property tax attorney based in New York City.

Tyler’s impact on local governments’ budgets will vary, according to Dave Lucas, the director of finance and intergovernmental relations for the New York State Association of Counties.

Over the past three years, Oswego County received an average of $1.2 million annually from tax foreclosure sales, said Gardner, who serves as the county’s treasurer. In the past, he said, the county has used some of that money to offset the cost of completing a foreclosure — like sending out delinquent notices and doing title searches. In 2023, it cost Oswego $111,000 to foreclose on 51 properties. It kept the remaining $1 million, and those funds will remain in an account until the county gets direction, Gardner said.

In 2023, Otsego County expected $650,000 in tax foreclosure sale revenue. Allen Ruffles, the county’s treasurer, said the loss of revenue will not have a major impact on the county’s budget. Instead, he is worried about “the legal and administrative headache that could possibly come with having to return surplus monies.”

Ruffles said that at least 75 percent of all properties the county takes to foreclosure are abandoned, or the owner is deceased and no living relatives could be found.

“How is my staff of three people going to do their daily jobs, which are burdensome enough, and research 50 to 60 properties to see who owns them, find addresses or phone numbers for them, and contact all of them?” Ruffles said.

In 2019, the city of Buffalo kept $3.6 million in surplus funds from the sale of tax-delinquent properties at an annual auction. The city set up a program for former owners to apply to receive the surplus funds — but it failed to ever deliver the money, according to Investigative Post.

To Dwyer, returning the payments is only just.

“Imagine that your life savings is going down the drain because you couldn’t pay $10,000,” she said.

AFTER THE TYLER DECISION in May, the majority of municipalities in New York paused all tax foreclosures to give the state time to amend its property tax law. In addition to local governments, that’s also affected New York’s 28 land banks.

While most New York municipalities sell tax-delinquent homes at public auctions, some transfer them to one of the land banks — non-profit organizations that rehabilitate tax-delinquent properties and sell them to vetted buyers.

The Syracuse land bank has sold 1,300 properties since it was created in 2012. By 2019, it had reduced the number of vacant buildings by at least 20 percent, according to Katelyn Wright, executive director of the Greater Syracuse Land Bank.

But some of the buildings’ former owners still live in them — around Syracuse, less than 10 percent, Wright said. The land bank does not typically sell the occupied property back to the original owner.

In 2022, the Albany County Land Bank acquired two properties — down from 200 to 400 properties in past years, said Adam Zaranko, its executive director, approximately 90 percent of which were vacant or abandoned.

“Everyone’s focused on homeowners, which is totally rational and the right thing, but the bad properties, the harmful ones, are caught up in that net,” Zaranko said.

“We deal with a lot of formerly redlined neighborhoods and we see a lot of minority homeowners who are losing equity when they get foreclosed on.”

The Tyler decision is also creating a money issue for land banks. Pre-Tyler, the city of Syracuse would sell a tax-delinquent property to the Syracuse land bank for $151, $150 of which covered administrative fees. The city would eat the unpaid taxes, figuring the rehabilitation of vacant and abandoned buildings justified the cost. Sometimes, land banks sell these properties to affordable housing coalitions.

A municipality “wouldn’t ever think to just allow the homeowner to stay for one dollar,” Dwyer said. “They would rather sell it to a nonprofit for one dollar, so they can create affordable housing. And the question is for whom? Because now you’ve made a family homeless.”

Now, under Tyler, land banks will be expected to pay the surplus —the remainder after taxes and administrative fees — to purchase the delinquent buildings. Then, the local government will return the surplus money to the former owner.

Despite the new challenges, Wright said Tyler is “a step in the right direction.”

“We deal with a lot of formerly redlined neighborhoods and we see a lot of minority homeowners who are losing equity when they get foreclosed on,” Wright said. “We need to be doing everything we can to reverse that.”

As the state works to amend the tax foreclosure process to follow the Tyler decision, the New York Association of Counties is asking lawmakers to consider investing money in counties to help prevent tax foreclosure. nysac is also asking for money from the state to offset the future losses from not being allowed to keep the surplus money from tax foreclosure sales.

“During covid, the federal government committed funding through the Homeowner Assistance Fund where they help keep people out of foreclosure or help pay their back rent, or arrears and utilities and water fees and things like that,” Lucas said. “I think it would be worthwhile for the state to do that as well.”

State Senator Sean Ryan, a Democrat from Buffalo, said there are currently several bills that have been introduced that he believes will be combined into one to restructure the tax foreclosure process in New York.

“That’ll include more notice to homeowners, allowing municipalities to take partial payments and reducing the interest rate charged,” Ryan said.

Before Tyler, Dwyer said she had no power to help foreclosed on homeowners get their money back. All she could do was tell her clients what was going to happen to them. In a post-Tyler world, she’s seeking fairness.

“We’re really just trying to get everyone to understand that this is not just about what they owe,” Dwyer said. “They already acknowledged they owe the debt. We need to treat them fairly too.”